Leiden physicists find way to control fractures

14 October 2016

If you are unlucky enough to have broken a limb at some point in your life, did you wonder why it was the bone that broke, and not the skin? After all, the skin took the first impact. From our intuition we know that rigid materials break more easily than soft ones.

Crack

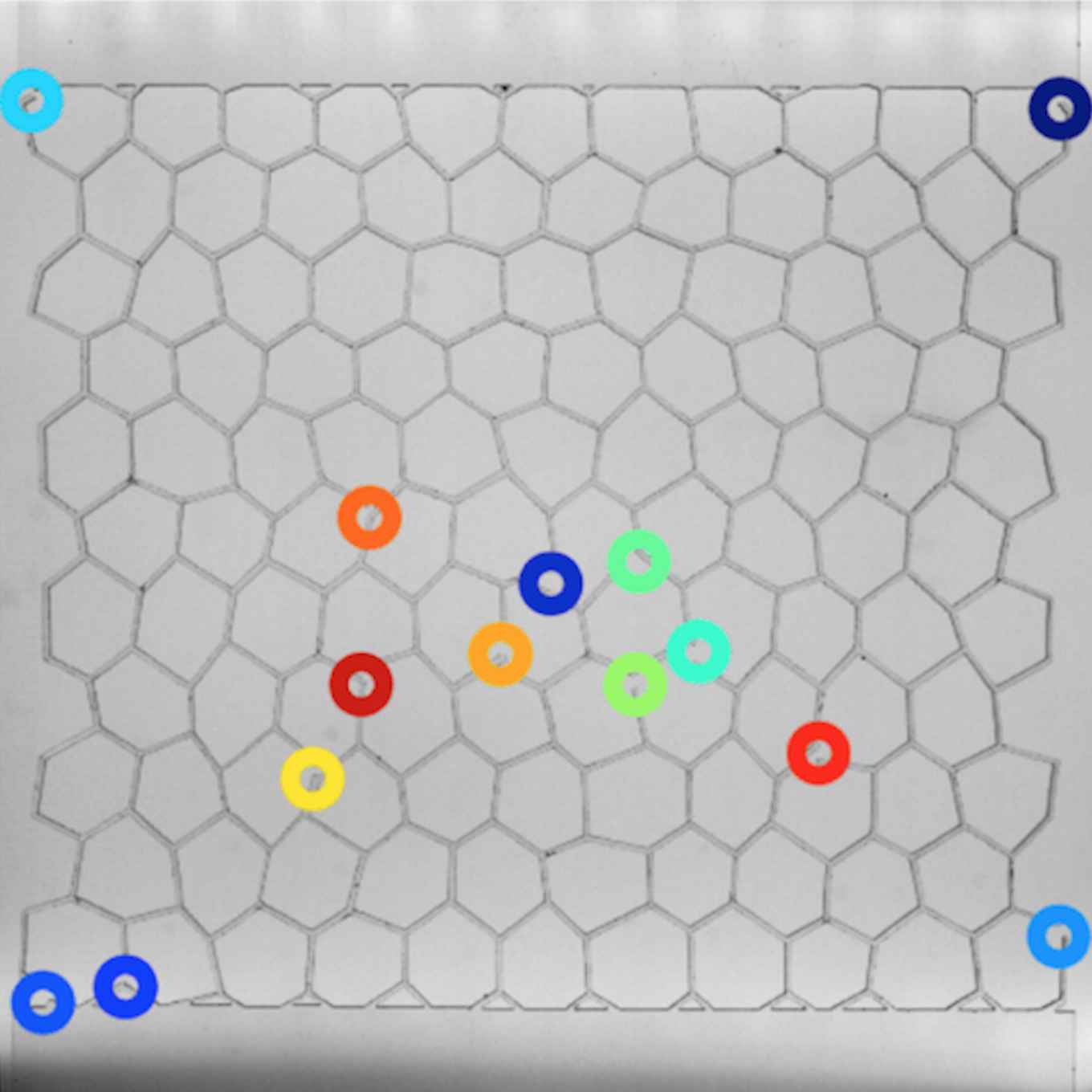

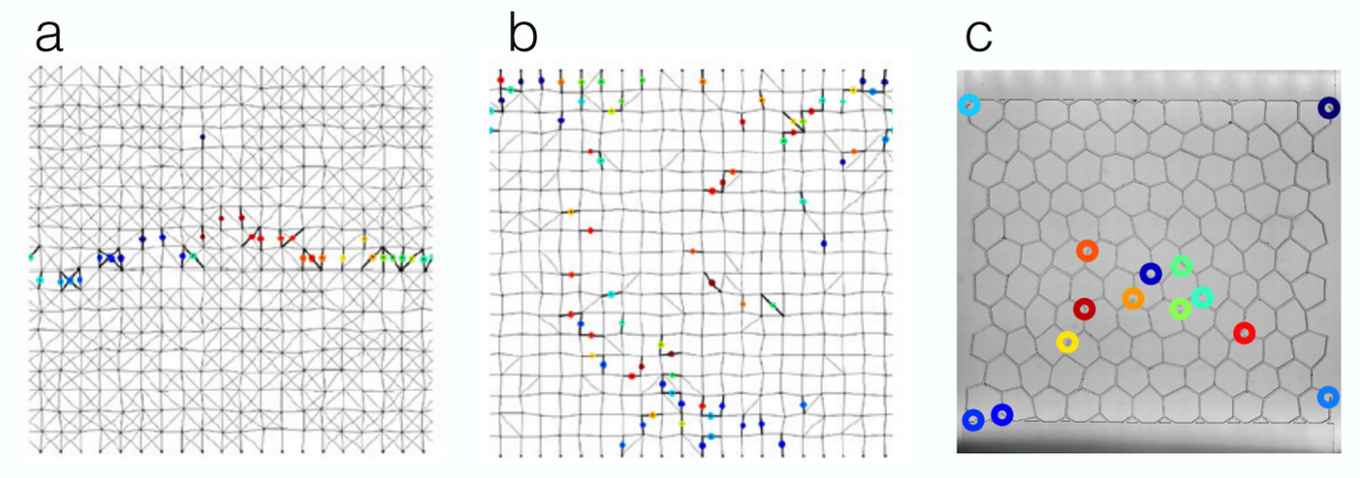

The research group of FOM workgroup leader Vincenzo Vitelli (Leiden University) and his colleagues from the Nagel Lab have exploited this phenomenon to design materials that resist breaking. A rigid material has many bonds and generates a narrow crack in an approximately straight line. A material composed of fewer bonds is softer and produces a diffuse failure region: a crack that can be as wide as the sample size. When that happens, the material can resist catastrophic failure thanks to its softness. To discover this, the physicists simulated and built artificial structures, called metamaterials, with tunable numbers of bonds that break in unusual ways. They published their findings in the journal PNAS.

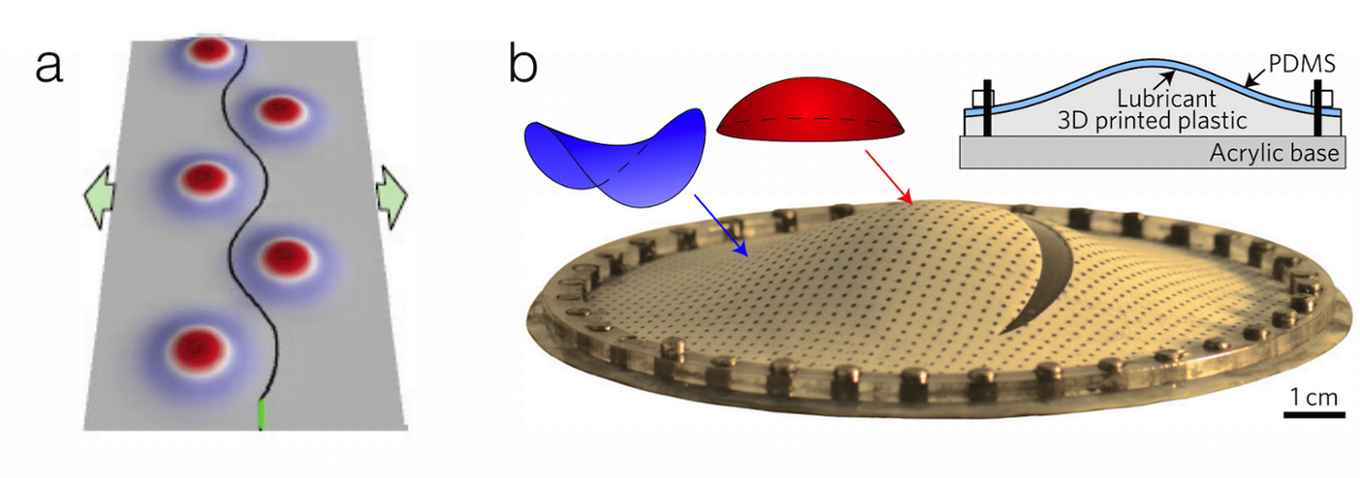

Einstein

Earlier, Vitelli's group published a paper in Nature Materials in collaboration with the Irvine Lab, on the path that a crack follows as it propagates in a curved thin layer. They discovered a remarkable parallel with Einstein's theory of general relativity, where a ray of light is bent by the curvature of space-time. In the case of fracture, the crack path is bent by the curvature of the underlying surface.

"When you have a theory on how things break, you can use it to control the properties of real materials," says Vitelli. "This is potentially useful. For example, you may want to deflect a crack from a portion of a given structure, like the centre of your glasses. Or, to prevent breaking altogether, you can design floppy metamaterials."

Reference

The role of rigidity in controlling material failure, Michelle M. Driscoll, Bryan Gin-ge Chen, Thomas H. Beuman, Stephan Ulrich, Sidney R. Nagel & Vincenzo Vitelli, PNAS